From the Dream of a Home Land to the Nightmare of Occupation The basic reason for the old conflict in Middle East bet of aween Israel and its neighbours is the fact that the Palestinians have had to pay for the historical sins committed by the Europeans against the Jewish people. How could that happen and how to reach a sustainable solution?

Sixty years ago, 1949, an armistice agreement ended the war between the new Jewish state Israel and its Arab neighbours. Although it wasn´t a peace agreement, it was still obvious for the world that a new independent nation was born – a home land also for the Jewish survivors from the holocaust. That in itself was for many people – especially for the survivors themselves – a miracle and the expectations were high. After several full scale wars – and after countless minor battles, bomb attacks, assassinations etc – Israel has managed to make peace

agreements with only two neighbours, Egypt and Jordan. And since 1967 – for more than forty years – Israel still occupies the West Bank, Gaza and the Syrian Golan Heights. How could it turn out this way? It started with a dream… For a long time Jews around the world during Passover (Pesach) used to greet each other with a ”Next year in Jerusalem”. This was, for a long period, only an expression of a dream, which hardly anyone thought could be realized and hardly any suitcase was ever packed. The background for this ritual is some thousand years old. The Old Testament in the Bible is mainly made up of stories about a small tribe living in what today is known as the Middle East, who, over three thousand years ago, started to worship one God. It is also the story about how Judaism became the first known monoteistic

religion, that is a religion with only one universal God. To what extent those biblical stories are true or not is of course in dispute. However, for believers, the Bible represents a kind of truth that is beyond question. According to that ”truth”, or myth, God is supposed to have chosen the Jewish people and also to have promised it that piece of land which today mainly consists of Israel, the West Bank and Gaza. According to the Bible, the Jewish people did indeed found a kingdom in that area about three thousand years ago, with the city Jerusalem as its political and religious centre. The Israelites were a small people, surrounded by several of the great powers of that time: Egypt, Assyria, Macedonia, the Roman Empire… Those empires tried – with various degree of success – to control the Israelites who, according to the stories, seemed to have valued freedom more than life. Accordingly, those empires were forced to suppress several uprisings and the punishment for the rebellious Israelites was a number of deportations from the ”promised land”. The last great uprising ended the year 135 when the Roman Empire defeated the insurgents and prohibited the Israelites from entering Jerusalem. Because of those recurrent deportations the Diaspora – the Jewish dispersion – developed until most

Jews lived outside their original homeland. The descendants of those exiled Jews spread over large parts of the world but continued to a great extent to celebrate their religious festivals, to follow their religious practices and to marry within the group. A small group of Jews continued to live in the ”promised land”, alongside other indiginous peoples who have lived there from before the Israelites arrived. An example would be the Philistines (which probably is the origin to the word Palestine). Later more people arrived and settled, such as Arabs who came with Islam in the seventh century or European crusaders who came with Christianity a few hundred years later. Jerusalem is regarded as a holy city for three faiths: for the Jews because that was the place for their

temple, for Christians because a Jew, Jesus, was chrucified there, and for Muslims because, from there and in a dream, the prophet Mohammed ascended to heaven where he met God. The ancient Jewish temple was destroyed by the Romans the year 70 AD and the only part remaining from that time is the so-called Western Wall (or Wailing Wall). Since 691 AD the Muslim Dome of the Rock and the neighbouring Al-Aqsa mosque are built on the site of the old temple. The central shrine for the Christians is the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which was built on the spot where it is thought that Jesus may have been chrucified. In the sixteenth century all the eastern coastal area of the Mediterranean was conquered by the Ottoman Empire, and it controlled those areas until the First World War

1914-18. During the last decades of the Ottoman Empire, the immigration of Jews to the ”promised land” increased inspired by a new popular movement among Jewish groups, chiefly in eastern Europe. It was known as the Zionist movement. The Zionism – a national movement The Jews in the Diaspora were always a minority, wherever they lived,

and religious minorities have often been exposed to oppression from majorities. The Jews in Christian countries were often accused of having ”murdered Jesus” for example (in spite of the fact that the crucifixion took place long time ago and was carried out by the Romans). After the Age of Enlightenment in the eighteenth century the situation for the Jews in western Europe gradually improved. However, in eastern Europe, especially in Russia, Jewish groups were exposed to frequent violent persecutions, so-called pogroms. Anti-Semitism, anti-Jewish hostilities, continued to thrive in Europe during the 20th century and reached its culmination with the Holocaust during the Second World War. However, at the end of the nineteenth century, a Jewish ”resistance movement”

arose in Europe – Zionism. Theodor Herzl was the driving force behind it. He argued that the only way for the Jewish people to respond to growing anti-Semitism was to create a state of their own, a homeland for the Jews. When most other people in Europe, aspired to become independent at that time it was only fair that the Jews should also get a state of their own. There were, however, two complications: Firstly, unlike most other groups the Jewish people did not live in one region but were scattered throughout Europe, indeed throughout the World. The solution was to aim to return to that region in the world – Palestine – where the Jewish people lived over two thousand years ago and from which they were expelled by the Romans. The new vision and the new popular

movement, Zionism, got its name from a hill, Zion, just outside old Jerusalem. At the first Zionist world congress, in Basel 1897, the Zionist goal was adopted. It stated that ”Zionism aims at establishing for the Jewish people a publicly and legally assured home in Palestine”. Secondly, Palestine was already a home for a people – the Palestinians. In the beginning that did not cause any major conflict, partly because the first Zionist immigrants were few, partly because they were so poor that they had to put up with settling in those areas, marshes etc, which were unoccupied. These areas were often bought with the help of donations from rich Jewish families in Europe, who themselves refrained from emigrating to the undeveloped and malaria-plagued ”promised land”.

Besides, a small community of Jews had lived in Palestine for centuries so, in a way, the arrival of small numbers of new Jewish settlers was no cause for alarm. Probably few immigrants – or other Europeans for that matter – ever questioned the right to settle in the country. At the end of the 19th century colonialism was at its peak and for Europeans it was almost self-evident that they had the right to settle everywhere outside Europe. For many, it was even seen as a mission, through which less developed peoples would get a share of the European culture and technology. Some among the Zionist leaders imagined the future homeland as a pluralistic country with the Palestinians as equal citizens; others dreamt of a Jewish state solely for the Jews. Besides, at that time, there were hardly any other alternatives than Palestine if the Jewish people should get a state of their own – and that need was difficult to argue against. ”A country without a people for a people without a country”? A well known myth is that the Jewish immigrants did not know that they arrived to a populated land, but thought that it was ”a country without a people for a people without a country”. That myth could possibly have been cultivated by Zionist leaders to facilitate immigration of ignorant Jews in Europe. However, for those who lived in Palestine it must have been clear what it was about. David Ben-Gurion, who became the first Prime Minister in Israel, 1948-1953 (and 1955-1963), at a meeting 1919 with the Zionist leaders stated that ””we, as a nation, want this

country to be ours; the Arabs, as a nation, want this country to be theirs”. (1) In an article 1923, ”Iron Wall”, the militant Zionist Vladimir Jabutinsky declared that a peaceful agreement with the Arabs was impossible, because they ”…look upon Palestine with the same instinctive love and true fervor that any Aztec looked upon his Mexico or any Sioux looked upon his prairie. To think that the Arabs will voluntarily consent to the realization of Zionism in return for the cultural and economic benefits we can bestow on them is infantile.” (2) However,

much later, after the establishment of the state of Israel, it was possible to live in Israel as a Jew without being conscious of, or, being reminded that 15-20 per cent of the citizens were and are Palestinian Arabs. That has among others Göran Rosenberg, a Swedish writer, showed (3). Two promises to two peoples… At 1880 there was a

population of about 400,000 in ”Palestine”, the area which today consist of Israel, the West Bank and Gaza and which, at that time, was a part of the Ottoman Empire. The majority were Arabs, or Palestinians, and most of those were Muslims. Approximately one fifth were Christians. Less than 25,000 were Jews and most of them had been living there for many generations. It was around this time that the first Zionist immigrants arrived, that is immigrants who looked on Palestine as the future Jewish homeland. Due to the Zionist immigration the Jewish population increased faster than that of other groups. At the outbreak of the First World War, 1914, the population in Palestine had increased to around 700,000, of which almost 100,000 were Jews. At that time the Arab

opposition to the Zionist immigration had started to grow, at the same time as the emergence of an Arab nationalism in opposition to the Ottoman rule. It became obvious for more and more Palestinians that the immigrating Jews not only sought a refuge from the persecutions in Europe but also aspired to create a nation of their own. During the First World War 1914-1918, Great Britain promised to support the Arab aspirations for independence in return for their support to the British forces in the war against the Ottoman Empire, which had sided with Germany and Austria. At the same time, Britain promised to support the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine (the so-called Balfour Declaration 1917) – under the condition that it would not violate the civil and

religious rights of other groups in the country. With that the government in London had put itself in a tricky situation, because the two promises comprised partly the same area, Palestine. British mandate with a Zionist vision When the First World War ended, the Ottoman Empire had lost all its dominions outside the main country, that is Turkey

of today. From the divided empire, about forty different countries would eventually be founded, such as Egypt and Syria. Some of those became so-called mandate areas after the war and were formally assigned either to France or Britain by the League of Nations. One of those areas, Palestine, became a British mandate in 1922 and it lasted until 1947. According to the mandate, Britain should – on behalf of the League of Nations – support the establishment of a Jewish homeland. The purpose of the mandate was ”…the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, it being clearly understood that nothing should be done which might prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political

status enjoyed by Jews in any other country”. Britain should also for example see to it that the Jewish community establish a council, for the British to cooperate with. (4) The British immediately got into problems with its Palestinian mandate. They wanted for example to set up autonomous institutions, according to the mandate, but did not get any local support. The Palestinians did not want to join any institutions together with Jews and the Jews did not want to participate in any cooperation where the Palestinians had a majority. Jewish social institutions During the interwar period the Zionist immigration continued to Palestine, at the same time as the Palestinian resistance continued to grow. Jewish immigration was driven, to some extent, by the growing persecution of Jews in Polen and other countries in eastern Europe during the twenties and later in Germany after the takeover by the Nazis 1933. With a fast growing Jewish population the number of confrontations with the Palestinians also grew. Now it was not only a

matter of small groups of poor Jews, settling in barren areas, who with mutual strength managed to get the ”desert to bloom”. Landed properties were bought from Arab landowners, who often resided in Beirut and other big cities, and the Palestinian tenants, who often had cultivated the land for generations had to move while Jewish immigrants took over. This was not a unique state of affairs for Palestine, but the fact that those who took over the land were immigrants with their own language and another faith intensified the antagonism. For at least some of the Jewish leaders it was obvious what it was about, as the following statement from David Ben-Gurion shows: ”…politically we are the aggressors and they defend themselves” (1). The relationship between the groups hardly became better by the policy among the immigrants only to employ other Jews and only to buy commodities produced and sold by Jews. The resistance against the Jewish immigration became more and more violent, as did the Jewish counterattacks. The British tried to reduce the violence by putting restrictions on the number of Jews that were allowed to enter Palestine, which made the Jewish community start organizing illegal immigrations. Britain also outlawed the establishment of more Jewish settlements than those already

existing. This resulted in illegal immigrants erecting simple outposts, ”Stockades and Towers”, overnight. The British were not allowed to demolish such ”established” settlements. The same tactics was later used by Israeli settlers on the West Bank after the victory in the Six-Day War 1967 (5). During this period the Jewish community also founded a number of social institutions, which came to become vital pillars of society. The most important was The Jewish Agency in Palestine (1929), which became the unofficial ”government” for all Jewish settlements. Other institutions were the trade union confederation, Histradut (1920), the health insurance fund, Kupat Holim (1912), and not the least Haganah (1920), a Jewish armed militia which later became the framework of

the future Israeli army. Two underground Jewish militias, Irgun and Lehi, were also formed and they would probably today be classified as ”terrorist organizations”. Periodically Haganah fought those militias because they were considered to endanger the Jewish community in Palestina by their assaults and assassinations. The UN partition plan and war After the end of the Second World War, 1945, the full extent of the Holocaust was revealed. The German Nazi regime had organized mass murder of Jews and other persecuted groups, such as gypsies. Approximately six million European Jews had been killed by the Nazis – in direct combat, in mass executions, through starvation and torture in labor camps (such as Buchenwald), through gassing in death camps (such as Treblinka) and through arbitrary killings. The Jewish organizations were anxious to bring the survivors from the camps to Palestine, maybe half a million. However, Britain was under pressure from Palestinians and Arab countries and it tried to restrict the immigration, which to a great extent was organized

illegally. At the same time Britain also had to fight the Jewish terror groups in Palestine, and finally the British government gave up and asked the United Nations (the successor to League of Nations) to resume the mandate. UNSCOP (United Nations Special Committee on Palestine), proposed that Palestine should be divided into two parts, one Jewish and one Arab (6). The UN General Assembly accepted this proposal in 1947 in Resolution 181 (7): that Palestine should be divided in approximately two equal parts, the borders being adjusted to where the majority of Jews and Palestinians were living. The religiously disputed cities, Jerusalem and Betlehem, were to have international status and be under the control of the United Nations. The partition plan did not reflect the actual population in Palestine, which at that time comprised about 600,000 Jews and approximately twice as many Palestinians. However, the plan presumed that the Jewish population would continue to grow through immigrantion and one aim was to create two equal countries which could be united in an economic union with open borders. The Jewish community accepted the partition plan but neither the Palestinians nor the Arab countries. The Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi wrote that the Palestinians could not understand why

they should have to pay for the Holocaust och why it was looked upon as ”…fair for almost half of the Palestinian population – the indigenous majority on its own ancestral soil – to be converted overnight into a minority under alien rule” (1). United Nations had neither the will nor the means to enforce the partition plan. Almost immediately it gave rise to the war which the Israelis call ”The War of Idependence” and the Palestinians ”The Catastrophe” (Al-Nakba) which was fought mainly during 1948. During the fightings, the Jewish community proclaimed the establishment of the Jewish state of Israel, May 14, 1948. The next day, May 15, Arab military forces from the neighbouring countries attacked the new state – on the pretext of supporting the

Palestinians. After some opening successes for the Palestinian militias they were defeated, together with the armies from the Arab countries. The fightings ended with a truce 1949, when Palestine was diveded into three parts: the Jewish Israel, the West Bank that was occupied by Jordan and Gaza that was occupied by Egypt. The armistice border between the forces were drawn on a map with green ink and became known as the ”Green Line”. The truce was no peace agreement nor did it lead to any permanent peace. However, the international community came to regard the Green Line as the actual border for Israel. Palestinian refugees Following the truce in 1949 it was clear that the persecuted Jews from Europe at last had got their own homeland, but not through any sacrifices on the part of those who had committed the atrocities. With the armistice line Israel became much bigger than the 55 per

cent of Palestine proposed in the UN partition plan. Instead Israel ended up with controlling 78 per cent of the disputed area. The rest – the West Bank and Gaza – was occupied by Jordan and Egypt, which among other things meant that the Palestinians didn’t get a chance to build up social institutions of their own, like the Jews had done before 1948. Jerusalem was divided in an Israeli Western part and a Jordanian Eastern part, the Old City within the walls being in the Eastern part. Jerusalem was proclaimed the capital of Israel, but this was not accepted by the international community. That is the reason why, even today, almost all foreign embassies are located in Tel Aviv. Another result of the war was that more than 700,000 Palestinian refugees had to leave their homes and, to a large extent, ended up in refugee camps in the lands surrounding the new state of Israel. According to the Israeli historian – and Zionist – Benny Morris, the war ended with less than half of the Palestinians living in their own homes; thus the majority had become refugees (1). Some of the Palestinians were forced to leave their homes by Israeli soldiers while others escaped for fear of being attacked or on request from Arab forces. For a long time it was a commonly embraced ”truth” in Israel that the Palestinian refugees left of their own free will. However, later historical research – by Benny Morris and others – have shown that the great majority was

forced to leave or frightened into leaving and that several hundred Palestinian villages were destroyed by the Israeli army. Another Israeli historian, Ilan Pappe, calls it ”ethnic cleansing” (8). Benny Morris agrees, but he is of the opinion that it was necessary in order to create a Jewish nation, ”…when the choice is between ethnic cleansing and genocide […] I prefer ethnic cleansing” (9). One of the most disputed questions in the conflict is if the Jewish leadership already before the war planned to expel the Palestinians or not – or if it was something that happened ”spontainously” during the course of war. In any case, the Jewish leaders prefered that there would remain as few Palestinians as possible in what was to become the new state of Israel.

For example, David Ben-Gurion said 1938: ”I support compulsory transfer. I do not see in it anything immoral” (1). Israel refused to let all the Palestinian refugees return – contrary to United Nation´s declaration of human rights. Israel offered to let 100,000 refugees to return or to let Gaza become a part of Israel with its 60,000 inhabitants and 200,000 refugees – but that did not please the other side (1). Those states where they had found refuge, for their part, refused to let them integrate with ther own population – with the exception of Jordan

where the refugees were offered Jordanian citizenship. A special UN-agency was established to finance and manage the refugee camps while waiting for a definite solution, UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East). Consequently, the refugee camps became permanent provisional institutions, where poverty and homesickness continued to thrive, and as a constant ”unsolvable” problem in all peace negotiations so far. However, some of the Palestinians remained within the borders of Israel and became a minority. They have been regarded as potential traitors by many Jewish Israelis, a group which can not be trusted when it comes to the conflict with the Palestinians and the Arab states. Because the war 1948 did not end with a peace agreement, there was no permanent peace. The fighting continued on a small scale, partly between Israel and the neighbouring states, partly between Israel and Palestinian guerillas operating from across the Green Line. The border of Israel, The Green Line, was regarded as a temporary arrangement – both by Israel and its neighbours. After all, the Zionist dream contained a much larger area; Palestine alone was considered too small a country for all Jews in the world. Immigration of Oriental Jews Until the foundation of Israel there were minority groups of Jews who had been living in all countries in Middle East and north Africa for many generations. Because of the conflict, the situation for those groups became more vulnerable, and in some cases they were expelled. At the same time Israel was anxious to strengthen its own population with more immigrants, both as manpower to replace those Palestinians who had become refugees, and to make the new state stronger

from a military point of view. It may be that Israel paid some of the Arab states to let their Jewish citizens leave for Israel. This resulted in an immigration to Israel of Jewish refugees from these areas of approximately the same scale as the Palestinian refugees from Israel. The arrival of these groups of ”oriental” jews did not go altogether smoothly. Firstly, Israel was a poor country and could hardly afford to take individual wishes into consideration when the new citizens were allocated places to live and work. Secondly, the new immigrants arrived to a country which had already been shaped according to European standards and institutions and which were unfamiliar for those with another background. Thirdly, it became apparent that the newcomers often were looked

upon with patriarchal benevolence, sometimes also with some contempt, by the established citizens of European origin – those who had fought both against the British and the Palestinians, who had grown up in an environment with a strong pioneering spirit and who also were burdened by the memories from the Holocaust. Continuous fightings The

continuous low-intensive fighting sometimes developed into full scale wars. The first becan in 1956 when Israel, with support from Great Britain and France, attacked Egypt and invaded Sinai. The British and French motive was to prevent Egypt nationalizing the Suez Canal, while Israel wanted to force Egypt to open the Suez Canal and the Tiran Straits in the Read Sea for Israeli ships, which had been closed to them by the new leader in Egypt, President Gamal Abdel Nasser (1956-70). Israel also wanted to pre-empt a feared attack by the Egyptian army which was being armed with new Sovjet weapons. At this time, the Israeli army, to a great extent, was forced to buy cheap weapons from surplus stocks around the world, which can explain why the general staff was eager to act before the Egyptians had learned to handle their new and advanced weapons. The UN and the US pressured Israel to return Sinai to Egypt. At the same time Israel received guarantees from the US that international waters, the Suez Canal and the Tiran Straits included, were to remain open for ships to and from Israeli harbours. A UN force, which included Swedish soldiers, was stationed on the Egyptian side of the border to prevent further attacks. Fatah, the Palestinian liberation organization, was founded in 1957 by Yasser Arafat amongst others. He, Yasser Arafat, originally came from Gaza. Fatah argued in favour of a new war against Israel and criticized President

Nasser of Egypt and other Arab leaders for their inability to help the Palestinians. Nasser, who had more far-reaching ambitions than to help the Palestinians, was hardly inclined to be guided by Fatah. Instead he set up another and more co-operative Palestinian organization, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). Syria, on their part, had moved away from their earlier cooperation with Egypt and began to support Fatah. This forced Nasser to take on a more aggressive stance towards Israel – which eventually lead to the Six-Day War 1967. The Six-Day

War – a triumph and a humiliation In the North, on the border between Syria and Israel, a low-intensity war was going on which was mainly about access to water. Israel started to build a central canal to divert water from the Kineret (Sea of Galilee) to agricultural areas in central Israel, while Syria and Lebanon tried to divert the tributary streams to the lake. It was a kind of positional warfare on small scale, where they shot at each others tractors and bulldozers on each side of the border. In the South, Nasser became more and more aggressive. He spoke

of crushing Israel. He ordered the UN troops to leave Sinai and closed, yet again, the Tiran Straits to prevent ships passing to and from the Israeli city Eilat at the Read Sea. United States did not manage to keep its promise made in 1956 which guaranteed free access for Israel to international waters. Some doubt wether the Arab states actually wanted a new war, but the rivalry between them, the rhetoric, the actions and the escalated tensions in both north and south led towards war. According to Benny Morris, Egypt planned to attack Israel on May 27th, but then broke off the plans – possible after warnings from the United States and maybe also from Sovjet Union (1). Israel could not afford to keep its army mobilized more than a short period of time and on the morning of

June 5th, 1967, Israel launched a surprise air strike which almost completely destroyed the Egypt air force. With total control of the air space Israel managed to swiftly seize Gaza and Sinai from Egypt, the West Bank from Jordan and the Golan Heights from Syria. When the Iraelis attacked Egypt on the 5th of June they did not seem to have ambitions other than that to ward off what they believed to be an acute military threat. Israel tried to avoid getting into a war with Jordan who was bound by an agreement to support Egypt. Despite this, on June 6th fighting began and Israel occupied East Jerusalem. The Israeli army appeared to be content with this victory and did not continue the offensive. However, when it became clear that the Jordanian army had withdrawn not only from

East Jerusalem but from all of the West Bank it took only two days for the Israelis to take control of all the area West of Jordan River. In the beginning the Israeli government didn’t seem to have any definite opinion about what to do with the occupied Palestinian territory – in sharp contrast to the settler movement that arose after this war.

Occupation instead of ”land for peace” The military victory gave Israel a ”strategic depth”, that is a land area between the densely populated centre of the country and the ”enemy”. The military and other security conscious people were hardly prepared to give up that area for less than a secure and reliable peace. Israel within the

Green Line is, according to classical military thinking, very vulnerable with its wasp-like ”waist” where the majority of the population lives. It is, for example, only 11 miles between Tel Aviv and the closest part of the West Bank. Regardless of how the political and military situation before the Six-Day War was assessed, it is obvious that the Ministry of Defence could hardly let the other side take the initiative. The Israeli air strike, which started the act of war, was therefore considered to be a military necessity. (A few years later, in 1973, it was Egypt´s turn to take Israel by surprise – but then the whole of Sinai was lying as a barrier between the attacking forces and Israel). The victory also meant that Israel became an occupying power. Since 1947 the

Palestinians and the Arab countries regarded all land that Israel controlled as occupied, but now Israel was seen as an Occupying Power by the rest of the world. In the beginning this was seen as an opportunity, because now Israel, suddenly, had something to trade for a sustainable peace, ”land for peace”. However, that was not a formula that appealed to all those on both sides who wanted everything: Israelis who regarded the West Bank as part of the historical ”Israel” and the opponents on the other side who saw all of Israel as occupied territory. The Israelis never gave any unambiguous offer of ”land for peace” – at least not officially – and the limited proposals they gave were rejected. Two Israelis – Idith Zertal (professor at the university in

Basel, Switzerland) and Akiva Eldar (editor at the Israeli newspaper Ha’aretz) – have in a book about the settlements (5) written about a missed opportunity to achieve peace. Mossad, the security service (the CIA of Israel), did a survey directely after the Six-Day War to determine the attitude amongst the Palestinian leadership on the West Bank towards peace. They found that most of the leaders were prepared to sign a peace agreement about a permanent peace between Israel and an independent Palestine without an army of its own. In a report to the government July 14, 1967, Mossad recommended that an independent Palestine should be established as soon as possible on the West Bank and in Gaza. Mossad also suggested that Israel should take the initiative to solve the refugee problem and lead an international project for rehabilitation of the refugees. However, the Israeli government wavered for, at the same time, it was subjected to pressures from those who intended to become

settlers. No one seems to have taken the recommendations from Mossad seriously. The future settlers – those who regarded the West Bank as part of a historical ”Israel” – did not waver and so got the upper hand by influencing the divided government. The opinions about the occupied Palestinian territory varied within the Israeli leadership, from establishing a Palestinian state under the protection of Israel to annexation, that is a formal incorporation of the area with Israel. An Arab top-level meeting in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, on September 1st 1967, agreed on a threefold No: No to peace, No to recognition of Israel and No to negotiations. With that declaration, they weakened those Israeli politicians who sought to trade ”land for peace”. The result was a continuous occupation and an annexation of East Jerusalem – an act that has not been approved by other countries. Half a million Palestinians were living within the occupied territory – a fast growing population who were not Israeli citizens – in contrast to the Palestinians who lived inside the Green Line. Those who lived in East Jerusalem were offered citizenship but few accepted. The rest of the Palestinians on the West Bank and in Gaza were never offered any Israeli citizenship, neither those refugees who originally came from areas within

the Green Line nor the others. To preserve Israel as a Jewish state presupposed that the non-Jewish citizens should remain as few as possible. ”… a cancer in the body of the Israeli democracy” Directely after the victory the Israeli government was subjected to pressure to permit Jewish settlements on the West Bank. The Prime Minister,

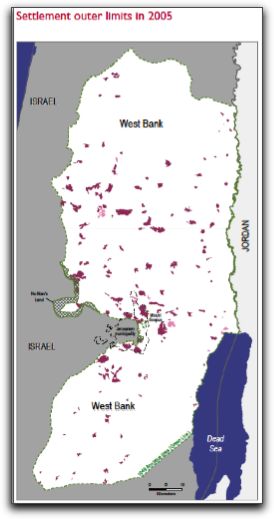

Levi Eshkol, gave his approval – maybe reluctantly – and within a month the first settlement was a fact. The ”decision” was taken – according to Idith Zertal och Akiva Eldar (5) – without the government considering what such a decision would involve in the long run. The settlers were, from the very beginning, united, single-minded and farsighted. The politicians in the government and in the Knesset (the Parliament) were, on the other hand, divided, vague and short-sighted – unless they supported the settlers. Their actions were often characterized by a remarkable naiveté regarding the real ambitions of the settlers. One of the naive leaders was Yitzhak Rabin (Prime Minister during two periods, 1974-77 and 1992-95), who saw the danger however and described the settler movement as ”…a very serious problem – a cancer in the body of the Israeli democracy” (5). The settler movement is composed of the most extreme settlers, those who are driven by a conviction that all of the West Bank (Judaea and Samaria in everyday Israeli language) was given by God to the Jews. For them, all that land is holy, or, as one of the religious leaders, Zvi Yehuda Kook, wrote in Jerusalem Post January 4, 1974: ”…all this land is ours, absolutely, belonging to all of us; it is nontransferable to others even in part”. As mentioned earlier, the actions of the settlers were clear and determined. Some of the leaders, however, had, in the beginning, somewhat naive hopes. They talked, for example, about getting two million settlers by the 1970’s, but numbers increaased to only slightly more than ten thousand and today, in 2009, the number is about half a million. There were not many settlers until it became really cheaper for Israelis to live on the occupied territory – and then they got another target group than the extreme Zionists. The change came after the election 1977, when the leader of the right-wing Likud party, Menachem Begin, formed a Government and when new and enlarged settlements became the official policy of Israel.

Several of the leaders in the settler movement are clearly charismatic persons. You could even say that the movement itself is ”charismatic”, because it presents itself as a bearer of the pioneer spirit which to a great extent characterized the first Zionists. The movement appeals to those who seek a higher meaning in life – those for whom becoming like other nations is nothing worth aiming at. With them, democracy is in no favour, even if they themselves use all the possibilities the Israeli democracy and freedom of speech offer. The settler organization,

Gush Emunim, which was established 1974, became not only a tool for settling on the West Bank but also a mean to force the state of Israel not only to be a homeland for Jews in the Diaspora but above all to fulfil a Biblical mission. War of attrition, Yom Kippur, peace agreement… At the Egyptian border, at the Suez Canal, a so-called war of

attrition went on during the years following the Six-Day War. Anwar Sadat, the new President in Egypt after the death of Nasser in 1970, alternated between making gestures for peace and threatening Israel with a new war. Golda Meir, the new Prime Minister of Israel, turned down any peace approach. The Israeli government obviously believed that they could afford to wait for the other side to submit to the Israeli demands and that they did not need to take the threats from Sadat seriously – a disastrous miscalculation which in the end forced Golda Meir to resign (10). On October 6th, 1973, during Yom Kippur, the most sacred day in the Jewish calender, Egypt attacked the Israeli positions at the Suez Canal. Egypt made considerable progress in the first days, but when Israel

started to mobilize there was no longer any doubt about which party had the strongest army. At the same time as the Egyptian army crossed the canal, Syria attacked Israeli positions on the Golan Heights, but there, also, the first days of success turned into a military defeat. Even though Israel managed to stop the assaults and regain the military initiative, the Yom Kippur War became a hard-earned victory: too many were killed and Israel realized that it, after all, was not invulnerable. The war thus became the beginning of a long process which ended with a peace agreement between Egypt and Israel in 1979 with Israel handling back all Sinai to Egypt in 1982. A few thousand Israeli settlers living in northern Sinai had to return to resettle inside Israel – on favourable

conditions. This was the first peace agreement made by Israel and it was not until 1994 that Israel managed to close the next peace agreement, this time with Jordan. This became politically possible thanks to the so-called Oslo Accords. Palestinians in a mess As a result of the Six-Day War the Palestinian liberation movements became more powerful, as they were no longer controlled by the defeated and discredited Arab states. Yasser Arafat, the leader of Fatah, became the chairman of PLO which, after the war, was recognized by all Arab states as the official resprentative of the Palestinian people. The PLO was recognised by the United Nations in 1974. The PLO had to handle both the fighting with Israel and its relationship with the Arab states where they had miitary bases and where many of the refugee camps were

situated. After a conflict with Jordan in 1970 the PLO was forced to move its headquarter to Lebanon, which became a base for attacks against Israel. The presence of the PLO made the tensions between the different factions in Lebanon even worse and this lead to the outbreak of the Lebanese civil war in 1975. The war was widened by invading troops, first from Syria 1976 and then from Israel 1978 and 1982. PLO was again forced to move, this time to Tunisia. Whilst the PLO and the other Palestinian organizations from the Arab states organized guerilla attacks and killings in Israel and against Israelis abroad, the Palestinians on the West Bank and in Gaza continued to live under occupation. The lull before the storm During the first twenty years of occupation there seemd to be peace on the West Bank and in Gaza: the borders between Israel and the occupied territories were open, many Palestinians worked on the Israeli side and the Palestinians in general experienced a fast economic growth and development. The traditional landowning

Palestinian elite adapted quickly to the new conditions. At the same time the Israeli settlements spread and became bigger, but support for the Palestinians from the Arab states seemed to dwindle. The trend indicated that the Palestinians were becoming an increasingly mariginalized group, living on a smaller and smaller portion of the land, while they would have to survive doing those works that were shunned by the Israelis. Glenn E. Robinson, reseacher at the Center for Middle East Studies at Berkely University in Californa, describes three changes in his book, ”Building a Palestinian State – The Incomplete Revolution” (11) by which the traditional elite on the Occupied Palestinian territory were gradually replaced by a new elite: Firstly, a large number of Palestinians, up to 120,000, obtained temporary jobs inside Israel at salaries which were less than what Israelis got but higher than the salaries in the occupied areas if indeed, there were any jobs avaiable. It was mainly small farmers who took those jobs and, in doing so, they became wage earners. This broke their traditional dependence on farming and landlords whose influence in society was weakened. Secondly, Israel gradually confiscated more and more land. This too undermined the old elite whose ownership of land was the base for

their prestige and power. Thirdly, the education system was enlarged. Before the Six-Day War there was no higher education on the West Bank or in Gaza, but, from 1972, several new universities were established. Tens of thousands of young Palestinians had, for the first time, access to higher education and from that group came a new elite. It was this group which in the eighties lead a political mobilization which turned aginst both Israel and the old Palestinian upper class. At the same time a gradual Islamisation took place on the West Bank and in Gaza with an

increasing number of new mosques, Islamic day nurseries and schools as well as clinics and charitable institutions. The First Intifada – predominantly a non-violent uprising In December 1987, the relative calm was broken when the first so-called Intifada (approx. ”shake off”) broke out – surprizing not only the Israelis but also the PLO

and the other Palestinian organizations, who were mainly based abroad. The First Intifada started as a spontanious popular uprising against the occupiers and it cracked the Israeli illusion about a benevolent and human occupation and about a possible coexistence on Israeli conditions. The Intifada was also an expression of the frustration over the growing gap between the Palestinians on the occupied territories and their self-appointed spokesmen abroad. The rebellion was carried out almost entirely by non-violent action; the most violent action being stone-throwing by Palestinian youth against the Israeli army. During the Intifada, 1987-1991, a little more than one hundred Israelis were killed (considerably fewer than during the five years following the Intifada). The

Israeli countermeasures were, however, more violent and during the same period almost 900 Palestinians were killed in confrontations with the occupying forces, while approximately 120,000 Palestinians, mostly youth, were inprisoned for shorter or longer periods. Many Palestinians received their first political training in Israeli prisons… Besides stone throwings, which made headlines in media around the world, the Intifada was mainly about organizing demonstrations, strikes, boycotts of Israeli shops etc. In the occupied Palestinian territory new local committees became responsible for planning such actions but, at the same time, planning for the maintenance of local services such as health care, garbage collection, distribution of food during the many curfews. They also

supported families when someone had been killed or imprisoned. Alternative education was organized during the long periods when schools and universities were closed by Israel. (As a collective punishments for political activity Israel forced schools and universities to shut down. During the first Intifada the universities on the West Bank were almost totally closed for four years.) The local committees also solved legal disputes since the ordinary judicial system had almost collapsed and the committees were also behind many of the executions of suspected Palestinian collaborators which took place during the first year of the Intifada. It goes without saying that sentences and punishments were not always handed out following due judical process. The committee system was a result of social mobilization. They, the committees, were lead by the new, growing, educated elite and they could have been the beginning of more permanent public institutions. However, the Israeli army realised that these new popular committees undermined Israeli rule and they were made illegal in August 1988. That did not stop the committees from functioning, but their character changed. They became increasingly dominated by political activist who were willing to risk several years in prison if they were detected. A few years later, after the Oslo Accords, the local committees were finally abolished – this time by the new Palestinian Authority lead by Arafat. There was also a ”national” committee which were responsible for the coordination and the overall leadership of the Intifada. It was finally crushed by Israel in March 1990 and, after that, the PLO leaders in Tunis, with Arafat at the head, took over the leadership of the uprising (11). It is difficult to come to any other conclusion than that the old leadership within the PLO made it difficult for a strong civil society to develop on the occupied territory. The traditional elite lost its influence through the social changes, but the PLO-leadership managed to keep its power. The same year the first Intifada started, Hamas was also created as a militant branch of the panarabic Muslim Brotherhood. The ultimate goal for the brotherhood is the establishment of an Islamic nation for all Muslims. Consequently it is regarded as a threat by most Arabic regimes. In the beginning Israel regarded Hamas as a counterbalance to PLO and, indirectly gave it some support. This was seen as a threat by the Palestinian left wing organizations. However, this ”honeymoon” ended when Hamas began to attack Israeli targets. A few years later, in 1994, Hamas too, along with Islamic Jihad, began suicide attacks. This was after an Israeli settler, Baruch Goldstein, assassinated 29 and injured 125 Muslims at prayer in a mosque at the tomb of Abraham in Hebron. Goldstein was killed during the attack, but has since then been honoured as a hero among the more radical settlers. The suicide bombings – so far a couple of hundreds attacks or attempts – have failed to push the Israelis closer to any peace agreement. Instead they have caused Israel to limit the opportunities for Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza to travel to Israel. This has caused grave economic problems for the Occupied Territory. The low payed jobs in Israel, which, during the seveties and the eighties, were done by Palestinians are today done by guest workers from the Philippines and other countries in East Asia. The suicide bombings have also heightened the Israelis’ fear of being close to Palestinians. This has widened the rift between the two people. The Madrid Conference after economic pressure In October 1991, a peace conference was held in Madrid where Israeli and Palestinian delegates met officially for the first time. This was the result of two decisive events: Firstly, in 1988 PLO decided to formally to recognize the UN resolutions which required Israel to leave the territories which it occupied during the Six-Day War in 1967. In doing so the PLO had accepted the right for Israel to exist and accepted that any future Palestinian state would have to be created on the West Bank and in Gaza, that is on 22 per cent of the old British Mandate. Secondly, in 1990 Kuwait was occupied by Iraq under the leadership of the dictator Saddam Hussein. The United States decided to liberate Kuwai but, to do so, it needed the support of other Arab countries. To get that support the US had to, more actively, try to persuade Israel to accept a peace agreement. To get all parties to the negotiating table was not easy. Initially the Israeli Prime Minister, Yitzhak Shamir, refused to participate, but Israel was in urgent need of an American guarantee loan in order to build houses for almost one million Jews who, at the beginning of the nineties, arrived in Israel from the disintegrating Sovjet Union. That gave the US president, Gerorg Bush Senior, the opportunity to force Shamir to choose between travelling to Madrid or to miss out on the loan. Shamir decided to participate in the conference where he, in contrast to the

Palestinians, continued to act as the reluctant partner with nothing constructive to contribute. The Madrid conference did not lead to any result, in line with Shamir’s plan. The following year, in 1992, when he lost the Israeli election, Shamir confessed that his aim had been to drag out the negotiations for ten years during which time he would fill the occupied Palestinian territory with more settlers (11). Nevertheless, the Madrid conference had some significance in that it made it possible for the next Israeli government to restart negotiations with the Palestinians. It became the first step towards the so-called peace process which began with the Oslo Accords a few years later. The Oslo Accord – the difficult questions unsolved After a period with right-wing dominated governments the Israeli Labour Party (the Avoda) won the election in 1992. Yitzhak Rabin again became Prime Minister. New settlements were cancelled, except for those in East Jerusalem, but existing settlements were allowed to expand. With Norwegian

assistance secret negotiations began between Israel and the PLO. These ended with the Oslo Accords in 1993 (12). According to that agreement, the Palestiniens should, during a transitional period, get limited autonomy on parts of the Occupied Palestinian Territory. During that period negotiations were supposed to continue with the aim of achieving a permanet peace and a ”two state solution”. The agreement meant that Israel acknowledged the PLO as the representative for the Palestinians on the West Bank and in Gaza, whilst the PLO recognized the right for Israel to exist within acknowledged borders. However, the question of where those acknowledged borders should be was postponed until later negotiations. It was the same with other complicated and contentious issues,

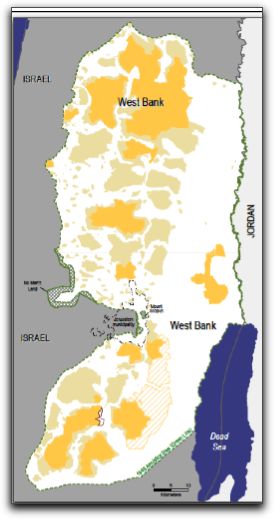

especially the future of Israeli settlements, the Palestinian refugees and the status of Jerusalem. A secure connection – a railway or highway – was to be constructed between Gaza and the West Bank, but, even now, no such connection exists. According to the Oslo Accords, the occupied territory should be devided in three areas during a transitional period of five years: Area A with full Palestinian control, Area B with Palestinian control of civil affairs and Israeli control of security and, finally, Area C with full Israeli control. Israel was also to control the borders to Jordan and Egypt. A consequence of this agreement was that the Palestinians in Area A and B, with the help of foreign aid, took over the costs for education, health care and other public services.

These were costs which Israel, as an occupying state, was obliged to cover. The negotiations about a final and permanent peace agreement – including the unresolved problems of, for example, refugees, settlements and Jerusalem – should start as soon as possible, but no later than 1966. The aim was to achieve an agreement which should take effect no later than 1999. The negotiations continued and a number of special agreements were concluded, about border controls etc. However, groups on both sides tried to thwart the peace process, Hamas and Islamic Jihad on the Palestinian side and the settler movement with the right-wing political parties on the Israeli side. The Israeli right-wing opposition started a hate campaign against Rabin, who, for example, was depicted in a

Nazi SS-uniform at a political rally in Jerusalem on October 5, 1995. None of the present politicians, including Likud’s new leader, Benjamin Netanyahu, protested and a month later, November 4, Rabin was assassinated at a mass peace gathering in Tel Aviv by a young admirer of Baruch Goldstein (the settler who, in 1994, murdered 29 Palestinians in a mosque in Hebron). During the election campaign which followed at the beginning of 1966, Hamas and Islamic Jihad continued their fight against the peace process with a number of suicide bombs. This resulted in the Likud party winning the election. Benjanim Netanyahu was elected Prime Minister in the new government and the former general, Ariel Sharon, became one of his cabinet ministers. The peace process more or less stopped and both sides accused each other for not complying with the Oslo Accords. It became obvious that the Israeli government had no intention of continuing the peace process but, preferably, making the Palestinians appear as the reluctant party. Instead, the settlements and the settlers continued to grow while yet more victims, both dead and injured, were claimed in a number of Palestinian suicide attacks and Israeli acts of vengeance. One might ask wetherif the Rabin government was, indeed, different from the following right-wing

government under the leadership of Netanyahu? Jeff Halper, coordinator for ICAHD (Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions), writes: ”It has become clear that no Israeli government has ever seriously considered relinquishing its control of the West Bank and East Jerusalem, certainly not in favor of a viable Palestinian state”. Regarding the Oslo Accords, Halper writes that it ”…became a trap for the Palestinians. It committed them to a ’peace process’ over whose content and priorities they had little influence, and one that left Israel free to strengthen its Occupation…” (13). It is also possible to argue – which Gleenn E. Robinson does in ”Building a Palestinian State” (11) – that the PLO, thanks to the Oslo Accords, strengthened its power on the

occupied territory. In the power struggle against the new popular elite, which arose among the Palestinians during the eighties and which became the leadership during the Intifada, Arafat and the old leaders in the PLO triumphed. New popular activists, those who were independent of Arafat, were systematically weeded out of Fatah, Arafat’s political base. indeed some of the old landowning elite – loyal to Arafat – got high positions in the new bureaucracy or in the new security system established in the self-ruling areas following the Oslo Accords.

The Second Intifada was much more violent In 2000, the president of United States, Bill Clinton, made an effort to reach a final peace agreement. The negotiations took part in Camp David, USA, between Clinton, Yassir Arafat and Israel’s new Prime Minister, Ehud Barak (Labour Party). The meeting failed; the Israeli team claimed that Arafat

received a very generous offer. This was denied by the Palestinian team – and by several other involved. According to Mustapha Barghouti, maybe the most respected of the Palestinian leaders among the public at large, the Palestinians were offered ”…a so-called state to be located on four separate cantons, with borders, airspace and water being controlled by Israel” (14). However, Barak managed to get the Israeli public to believe there had been a ”generous offer”, which implied, yet again, that it was the Palestinians who were totally unreasonable in rejecting the offer. Soon after the break down in talks at Camp David, the Second Intifada (or the al-Aqsa-uprising) began. This was, at least, partly provoked by the new leader of Likud, Ariel Sharon. With a large security guard he paid a visit to the Tempel Mount in Jerusalem – al-Sharif, Islam's third most holy site – where the mosque al-Aqsa stands. There are different opinions as to wether the Second Intifada was planned beforehand or not. However, Sharon’s visit was a sufficiently strong provocation to start a rebellion and, yet again, it was possible to present the Palestinians as unreasonable. The Second Intifada was much more violent than the first, partly because, following the organization of a Palestinian police force in

the autonomous areas (Area A), there were a considerable number of weapons on the Palestinian side. During the Intifada, which in most places was considered to have lasted until 2005, the occupied Palestinian territory was plagued by countless attacks and assassinations, retaliations, army intrusions, house demolitions etc. Because of the increased violence and because of the failed negotiations in Camp David – many Israelis lost faith in a peaceful solution and many in the Israeli peace movement (Peace Now!) became disillusioned. At the election in 2001 the Israelis voted in a new right-wing government, dominated by Likud, and Ariel Sharon became Prime Minister. The Second Intifada lead to serious economic setbacks for the Palestinians on the West Bank. According to a report from World Bank in 2007, the income per head decreased by 40 per cent between 1999 and 2006 (15). Israel, too, was affected. Shlomo Swirski, manager for the Adva Center in Tel Aviv, wrote 2005: ”The second intifada has hurt Israel deeply — the cessation of economic growth, lowering the standard of living, debilitating its social services, diluting its safety net and increasing the extent and depth of poverty. Israel comes out of the present intifada a more divided and less cohesive society” (16). A number of negotiations and further peace initiatives did not lead to any solution. At a meeting in 2002 the Arab states accepted a Saudi Arabian proposal for a peace plan. In it they offered peace with Israel in return for the territories that were occupied 1967 and a ”fair” solution of the refugee problem – that the refugees would be allowed to return or, alternatively, they would receive financial compensation for their lost properties. The proposal was rejected by Israel (17). Hamas responded with a new suicide attack and Israel, in turn, assaulted the Palestinian administration and re-occupied those areas which, according the Oslo Accords, should have had limited self-goverment. The so-called Quartet – United States, Russia, European Union and United Nations – then put forward a new peace plan in 2003, a ”road map” (18), which aimed at establishing a Palestinian state by 2005. Both sides agreed to accept

the road map, but the conditions on the ground did not improve. The wall During the second Intifada Israel started to build a 450 mile long wall or barrier to prevent ”terrorists” from the Occupied Territory entering Israel and to prevent the increasingly common thefts of cars, sheep etc. In more densely populated areas the barrier is a

wall, build of reinforced concrete blocks, up to nine metres tall. In other parts the barrier is a system of fences, barbed wires, trenches, patrolling roads and watchtowers – 50 to 70 metres wide. In November 2008, according to the United Nations, about two thirds of the barrier was completed. Most of the barrier is build on the Palestinian side of the internationally recognised border, the Green Line. That is the reason why the International Court of Justice (ICJ), in 2004, declared the wall to be illegal according to International law (19). The construction of the barrier has been made so that larger Israeli settlements have ended up on the western side of the barrier (approximately eight per cent of the West Bank has ended up or is planned to end up on the western

side). Because of this a number of Palestinians have also found themselves living on the western side of the wall and so cut off from the major part of the West Bank. In some cases Palestinian villages have been divided so that the village itself is on the eastern side of the barrier while large parts of the village’s agricultural land is on the western side, where the land owners have limited access to their fields. Only 18 per cent of the Palestinians who used to work in the fields had permission to work there after the barrier was erected and before 2007 (20). When, and if, the barrier is completed about 60,000 Palestinians in 42 villages will end up living between the barrier and the Green Line (21). Despite the fact that the barrier has been constructed in

violation of international law, its purpose, that is ”security”, has also been questioned. However, statisticts indicate that it might be effective; a similar barrier between Israel and Gaza also appears to have prevented infiltrations. Continuous occupation… The Occupation and the settlements are dependent on each other. The Occupation

makes it possible for Israelis to settle on the West Bank; the settlements on the other hand give cause for a continuous occupation. As mentioned earlier there are, according to Israel, military reasons for keeping a ”strategic depth” – but it would be enough to achieve that aim by surveying the border to Jordan. Since the first Intifada – and even more since the second – the Israeli control of the Palestinians has changed: Firstly, the West Bank (excluding East Jerusalem) is split up in a number of enclaves according to the Oslo accords: • 17 per cent is part of Area A; areas which are supposed to be governed by the Palestinians. Half of the Palestinian population lives in Area A. • 24 per cent belongs to Area B, areas which are administered by both the Palestinian Authority (for civil issues) and Israel (for security issues). • 59 per cent is part of Area C, land which is totally

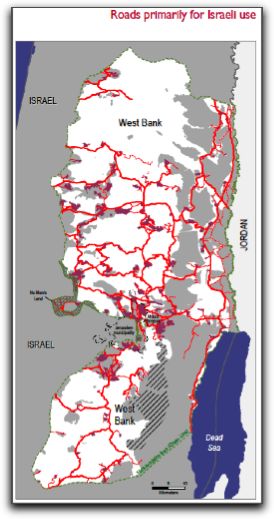

controlled by Israel. The Israeli settlements are in Area C and also all land which has been confiscated by Israel for military use. Secondly, the freedom of movement for the Palestinians is restricted by a system of almost a hundred manned military checkpoints, a large number of unmanned roadblocks, separate roads for Palestinians and Israeli settlers and the barrier/wall. One aim of which is to separate Israeli settlers and Palestinians as far as possible to avoid direct confrontations. Travels between the different parts of Area A often take a long time,

partly because of the checkpoints which have to be negotiated, and partly because of the detours Palestinians often have to make as some roads are reserved for Israelis only. Accordning to UN-OCHA, the fragmentation of the road network is a basic reason for the economic decline on the West Bank (21). In June 2009, the Israeli government decided to ease the situation at several checkpoints on the West Bank, primarely around four big cities: Nablus, Ramallah, Qualqiliya and Jericho. The reason given was that the Palestinian Authority was introducing much tougher measures to control supporters of Hamas and Islamic Jihad. Palestinians have very limited possibilities to travel to Israel. Every day around three thousand Palestinians pass through the wall, mainly at Betlehem, to work in East Jerusalem. To have a reasonable chance to reach their work in time they are queuing at the security control by four o’clock in the morning. Every morning it takes around two and a half hours to pass the wall into Israel. Thirdly, Israel exercises control though building permits and house demolitions. According to UN-OCHA more than 18,000 Palestinian buildnings have been destroyed since the beginning of the occupation 1967 (and since the Oslo Accords only within Area C). The reasons given are varied. For example, a building may

be to close to the Wall or it may have been built without a permit. For Palestinians in Area C, however, building permits are almost impossible to get. According to UN-OCHA, only six per cent of all applications for building permits have been approved by the Israeli authorities between January 2000 and September 2007 (21). However, there are obvious illegally built houses which almost never are demolished, houses build by settlers… And there are other illegal activities taking place. According to ICAHD (The Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions) over two

hundred thousand olive and fruit trees have been destroyed, or uprooted and stolen from the West Bank (13). The occupation has its own logic. It is very difficult for Palestinians to get permission to travel to Israel but, according to the Israeli daily news paper Haaretz (2009-02-03), it is almost impossible for those who have been injured by the Israeli army or by settlers, since they are regarded as potential avengers and therefore as serious security risks. Another such logic is the relationship between settlers and Palestinians. If settlers illegaly (according

to Israeli law) build a so-called outpost on the West Bank, security measures around the outpost affect the neighbouring Palestinian population. Also, if settlers attack Palestinians, then the army might close checkpoints, which affect the Palestinians but not the settlers who caused the problem. Following the murder of 29 Palestinians by Baruch Goldstein in 1994, the army issued a curfew in Hebron affecting tens of thousand Palestinians – but no limitation was imposed on the four hundred settlers in the centre of the city. The international community regard Israel’s control of the West Bank and Gaza as an Occupation, despite the limited self-government allowed (which, by the way, does not prevent Israel from entering these Palestinian self-governing areas with military

forces when they are searching for suspected ”terrorists”). The Israeli government, on the other hand, maintain that they ”administer” the territory with reference to the unsettled legal status of the area before 1967 when the West Bank was occupied by Jordan and Gaza by Egypt. In practice, this means that Israel does not accept that the Fourth Geneva Convention from 1949, regarding protection of civilians during war, is applicable to the West Bank and Gaza (22). …and more and more settlements Today, 2009, about half a million Israeli settlers live on the West Bank (479,500 at the end of 2008). It is common to read statements stating that there are about 300,000 settlers, but the settlers living in East Jerusalem are not included in this figure (East Jerusalem has been annexed by Israel in violation of International Law). During 2008 the number of settlers in the West Bank (excluding East Jerusalem) increased by 4,7 per cent compared with an increase of 1,6 per cent for the total Israeli population (23). In general there are three main groups of

settlers: 1. ”Economic” settlers, that is settlers who mainly have chosen to live on the West Bank because the houses are cheaper than in Israel. A comparison from 2007 shows, for example, that a four room apartement in the settlement Har Homa in East Jerusalem cost from 799,000 NIS whilst, at the same time, a three room apartemtn in West jerusalem was offered for 1.615 000 NIS (21). The ”economic” settlers are regarded as relatively easy to move volontarily – providing they are given other houses or apartements in Israel on the same favourable conditions. 2. ”Ideological” settlers – religious and nationalistic settlers – who regard Samaria and Judea (as the West Bank is called in Israel) as parts of the ”promised” land given to them by God. These ”ideological” settlers are maybe a fifth and the more zealous maybe five per cent of all settlers. It is unlikely that these settlers would ever agree to move. From time to time the more fanatical of them express more or less covert threats of civil war if they were forced to leave. 3. Less than half of the total number of settlers live in East Jerusalem. These do not recognise themselves as being ”settlers”, because they accept the annexation of that part of the city taken from

Jordan in 1967. These settlers can be both ”economic” and/or ”idological”. According to UN-OCHA there are 149 settlements which are established in compliance with Isareli law (21). In addition there are about a hundred smaller so-called settler outposts, which are illegal under Israeli law but nevertheless allowed to remain. Consequently, the 149 ”ordinary” settlements are regarded legal in Israel. However, a number of recent reports, such as the ”Spiegel Report” (2009) from the Minister of Defence, show that large areas of these ”ordinary” settlements are illegal according to Israeli law as private Palestinian land has been taken for building synagogues, schools and even police stations. The Israeli newspaper Haaretz calls it ”land theft” (24). All settlements are illegal according to international law (25). The Fourth Geneva Convention (22) expressly prohibits an Occupying State from moving its own population into Occupied territory. In this case, citizens of the Occupying State (Israel) should not settle on Occupied territory (the West Bank). In defence of the settlements Israel maintains, that it is not an Occupation and that the settlers move there from choice. It is true that no civilian Israelis have been forced to move to Occupied territory – but, as mentioned previously, they have been tempted to move by the offer of various economic benefits and the land used for settlements has not always been obtained legally. Furthermore, the settlements have lead Israel to build up an extensive infrastructure of roads reserved for Israelis, military blockades and checkpoints. This physical infrastructure – together with the administrative restrictions on the movement of Palestinian – has created a Palestine which, for the Palestinians, is criss-crossed by physical and legal obstacles. Most incidents and cases pf unprovoked violence by Israeli settlers against Palestinians are never reported by the media, but some attract attention. For example, in December 2008, a large group of

settlers in Hebron attacked a Palestinian family – a case which the then Israeli Prime Minister, Ehud Olmert, described as a ”pogrom” (the term used for violent persecution of Jews in especially old Tsarist Russia). The Palestinian family was rescued by a group of Israeli journalist, while the army did nothing. Incidents of violence by settlers are not uncommon. For example, in the middle of May 2009 UN-OCHA reported that the week May 6-12 was unusually calm with only one injured Palestinian – compared with an average of 17 injured every week during the previous month (26). Palestinian self-government and division There are approximately 4 million Palestinians in the Occupied Palestinian territory – 2,5 million in the West Bank and 1,5 million in Gaza. In addition there are about half a million Israeli settlers also living in the West Bank. According to UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East), there are a total of 4,6 million registered Palestinian refugees (more than 1,3 million in refugee camps). Of those

Palestinians who live on the West Bank, more than 750,000 are regarded as refugees. Of the 1,5 million living in Gaza, more than one million are refugees. The other refugees – more than 2,8 million – live mainly in Jordan, Lebanon and in Syria (27). The self-governing Palestinian areas, which were created in accordance with the Oslo Accords, consist, on one hand, of Gaza and, on the other hand, of those areas in the West Bank which form Area A (17 per cent) and those areas which constitute Area B (24 per cent), where the Israelis are responsible for security. The Palestinian National Authority (PNA or PA) was established 1994 with a mandate to govern those areas. The first elections in the self-governing areas took place in 1996. Fatah became the biggest party and

Arafat became the first President in the new ”state”. Arafat’s period as President was characterized by typical authoritarian rule with corruption, control of media, and the use of torture against Palestinian opponents (11). Arafat died in 2004 and was succeeded by Mahmoud Abbas as leader of the PLO and, the next year, as Palestinian President. At the election 2006 the Islamic Hamas defeated Fatah, probably because of corruption and abuse of power within the Fatah-dominated government. According to the constitution, Mahmoud Abbas continued as President, but

Fatah refused to take any part in a government alongside Hamas because Hamas refused to respect earlier agreements with Israel. Due to this refusal, all international support to the Hamas-lead Palestinian government was cancelled – despite the fact that Hamas was democratically elected by a fair process according to international observers. This boycott lead to an acute financial crisis for the government because of its strong dependence of foreign aid. The rivalry between Fatah and Hamas almost led to a full-scale civil war before Hamas took power in Gaza and Fatah formed a government for Area A and B on the West Bank. Ruthless purges against opponents took place on both sides. The President, Mahmoud Abbas, is formally president of both parts, Gaza and the West

Bank, but in reality only for the self-governing areas on the West Bank. And the rivalry between Fatah and Hamas continues. That does not mean, however, that the Palestinians are united within these two camps. Fatah is split between those who seak reconciliation with Hamas and those who do not, and similar division exists within Hamas. Hamas government in Gaza In contrast to the West Bank, Gaza has never been considered a historical Jewish area and there were, at most, only about 8,000 Israeli settlers. All settlers had to move from Gaza in 2005, following a unilateral decision by the Israeli Prime Minister at that time, Ariel Sharon. However, the evacuation did not mean any real independence because Israel continued to control all borders to Gaza, on land, at sea and in the air. Israel allows only a limited foreign trade – even the import of books is prevented according to the Swedish newspaper ”Dagens Nyheter”, June 3, 2009. Also, it is almost impossible for the people in Gaza to leave what has been called ”the worlds biggest prison” (28). Gaza is a locked and

strictly controlled enclave. Because of the blockade, the limited trade which Israel allows and the frequent attacks by Israel in retaliation for the firing of rockets from Gaza into Israel, living conditions in Gaza are appaling, with an unemployment rate of around fifty per cent. However, the conditions are not as miserable as they might have been had mot many tunnels been built under the border to Egypt. Weapons are ”smuggled” into Gaza through these tunnels, along with basic necessities and other goods. Because the Islamic Hamas does not recognize Israel’s right to exist, its government is not only locked in physically but it is also politically isolated – even by parts of the Arab world who do not want to se a victorious Hamas becoming an inspiration for

Islamic groups in other countries. Hamas also seems to have lost some of the original support from the people in Gaza because of its uncompromising policy towards Israel, because of its ambition to build an Islamic society and because of its policy of firing rockets against Israel which leads to devastating counter attacks as occurred during the winter of 2008-09. On the other hand, Hamas has the support of other Islamic fundamentalistic groups in the Middle East. In a similar way to fundamentalistic Jewish groups, who regard all land from Jordan River to the Mediterranean as given by God to the Jews, so Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood regard Palestine as part of a larger area given to them by God. Consequently, it is inconceivable that any of these groups will give up

part of the land to others. Fatah government on the West Bank The government of the self-governing areas in the West Bank is dominated by Fatah, but is also made up of other smaller parties. Unlike the Hamas government in Gaza, the Fatah government has acknowledged Israel’s right to exist and there is limited cooperation with Israel – but

it’s a ”cooperation” on Israeli conditions. The Palestinian Authority walks a tightrope between pressure from outside and from inside. On one hand it is bound by the Oslo Accords and under pressure from Israel – and the US – to fight ”terrorists”. On the other hand it does not want to appear as an Israeli puppet – which it to a great extent has already become – as it has taken over the responsibility, and the costs, of combatting Israel’s enemies in Area A. The Palestinian Authority is free to act in this area of security without reference to the Supreme Court or to human rights organizations in Israel – a fact that appeals to the Israeli army. Abuse of power and corruption have been very common, but appear to have diminished since Arafat died. At the same time security has improved, both among Palestinians in the West Bank and also for Israelis because the Palestinian Authority strikes hard on all suspected ”terrorists” and tries to control the use of weapons. In spite of the reasonable acceptable elections there are still, however, some democratic shortcomings. The most serious perhaps are weak social institutions. Walid Salim, The Centre for Democracy and Community Development in Jerusalem, writes for example: ”The Palestinian

leadership has not been capable of building the nucleus of an independent state. Neither institution-building nor the separation of powers has proved a success as claimed.” (29). Another democratic weakness is the Palestinian Authority’s dependence on foreign aid which, in practice, means that its relations with foreign donar states risks being more important than the relations with its own people. ”Palestine” is a state in the making. At present it lacks liberal political traditions and essential democratic institutions. In Israel, all these traditions and institutions exist – but groups of the population refuse to respect them with no major protest from the majority. Israel – a democracy in question Israel has about 7,5 million inhabitants, inclusive the half million living in settlements on the West Bank. About 1,5 million are Israeli Palestinians who live inside the Green Line and who are citizens of Israel. It’s possible to stay in Israel for a long time without seeing, at first hand, anything